"The Little Monster Inside Me" by Karen Browne

- Feb 19, 2023

- 12 min read

An MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) scanner has a little secret that only those who’ve been scanned know about.

The time spent waiting for my name to be called was less than calming as I overheard more than one person being told they’d have to come back another day and be sedated for the scan. It made me wonder if it was a good idea to have an MRI even though I’d been waiting over a year for the appointment.

Eventually a woman in a technician’s white tunic called my name and escorted me down a corridor, through a set of double doors and into a room that held the MRI. It looked huge and yet the bed she pointed at was incredibly narrow.

As I lay down, the technician started warning me about how important it was to stay still. She gave me ear plugs and then pieces of foam were tucked behind and beside my head. She looked down at me, holding up what she called a panic button and I felt her putting it in my right hand. She told me to use it if I felt I was going to move suddenly or cough or couldn’t cope with the confinement. Then a cage was pulled over my face and I felt suddenly imprisoned.

She gave me one last smile, pressed something on the machine and the bed began to move inside the narrow tube. It was almost impossible to suppress the sense of panic at being so confined with no way out and no idea what to expect.

The beginning of the scan sounds like a metal ping pong ball is being bounced around every part of the machine and then it starts to make a noise that I can only compare to a pneumatic drill. The earplugs were completely useless. The noise scared the absolute shit out of me and I closed my eyes tight focusing on what felt like the mammoth task of staying still.

All of a sudden the thunderous roar stopped and I heard a speaker crackle in the vicinity of my head. A reassuring voice told me that I was doing well and that the scan would begin again in thirty seconds and last for two and a half more minutes. I rolled my eyes back, trying to see the speaker and spotted the MRI’s little secret, a mirror that showed the booth with the technicians coming and going, clutching files.

I also saw a woman sitting near a microphone and assumed it was her speaking. Her voice would come through the speaker during every quiet interval. I took each one as an opportunity to roll my eyes back and glance at the mirror to see what was happening in the booth.

Back in 1998, MRI’s were a rarity in Ireland and I had turned eighteen and completed my first year of university waiting for the appointment day to arrive. I was put on the waiting list after an epilepsy diagnosis, but lying in the tube, I doubted whether it was necessary as my seizures were well controlled with medication.

When the reassuring voice said the test was halfway through, I rolled my eyes back and saw a very different looking booth. It was filled with people, some in uniforms, some in scrubs and some in suits. They all had one thing in common, each was staring at a screen that had an image of my brain on it. As the scan went on, I kept looking in the mirror, hoping that the booth would suddenly empty, that all those people had gathered for a few minutes for some other reason, but each time I looked, there they all stood, focused on the problem of my brain.

After what felt like an eternity the scan finished and I emerged from the tube. I knew from the way the technician looked at me that something was wrong. She walked me to a different waiting area to my parents. A doctor appeared and said that there was something of concern on the scan. I was put in a wheelchair and told that I needed skull x-rays. The doctor remained with my parents while a porter whisked me away. I found this incredibly frustrating because I knew an explanation was being given to my parents and not to me, despite the fact that I was eighteen.

When the porter brought me back, I knew from one look at my parents that it was serious. A brain tumour, my mother said. I was to be admitted as an emergency through Accident & Emergency and the neurosurgical team would see me later in the day. I remember walking ahead of my parents through the main foyer of Beaumont Hospital with tears streaming down my face. I found it almost incredulous that I had something growing inside my head. Something so dangerous that I couldn’t go home.

It was a beautiful summer’s day, the heat was high and the sun shone in a cloudless sky. Being able to stand outside in the summer sun was a vital reprieve. Waiting in A&E was the same then as it is now, long, boring and overcrowded. The simple truth is that not enough has changed in the health service.

Late in the evening, a bed was found for me in the hospital’s renal ward and I would wait there until a bed became available on the neurosurgery floor. It was terrifying and I recall feeling terribly alone once my parents left for the night. A woman in the bed opposite me came over and asked how I was and why I had none of my things. When I explained the emergency, she offered me a pair of pyjamas and something to read. She also introduced me to something that is now long gone from any hospital, the smoking room. To this day, I can remember telling a fellow smoker that something had been found in my head, but nobody was sure what it was. With hindsight, I doubt that was the case, it was just that it hadn’t been explained to me.

After a few days, I was moved to the neurosurgery floor where I met different members of the team looking after me, but no serious conversations were had with me. They spoke with my mother in the corridor in hushed tones and I will never know how much or how little information was passed on to me. My mother did what any mother would do in such a situation, she erred on the side of protecting me. I’m no longer able to ask her what she remembers about those days because she passed away a number of years ago.

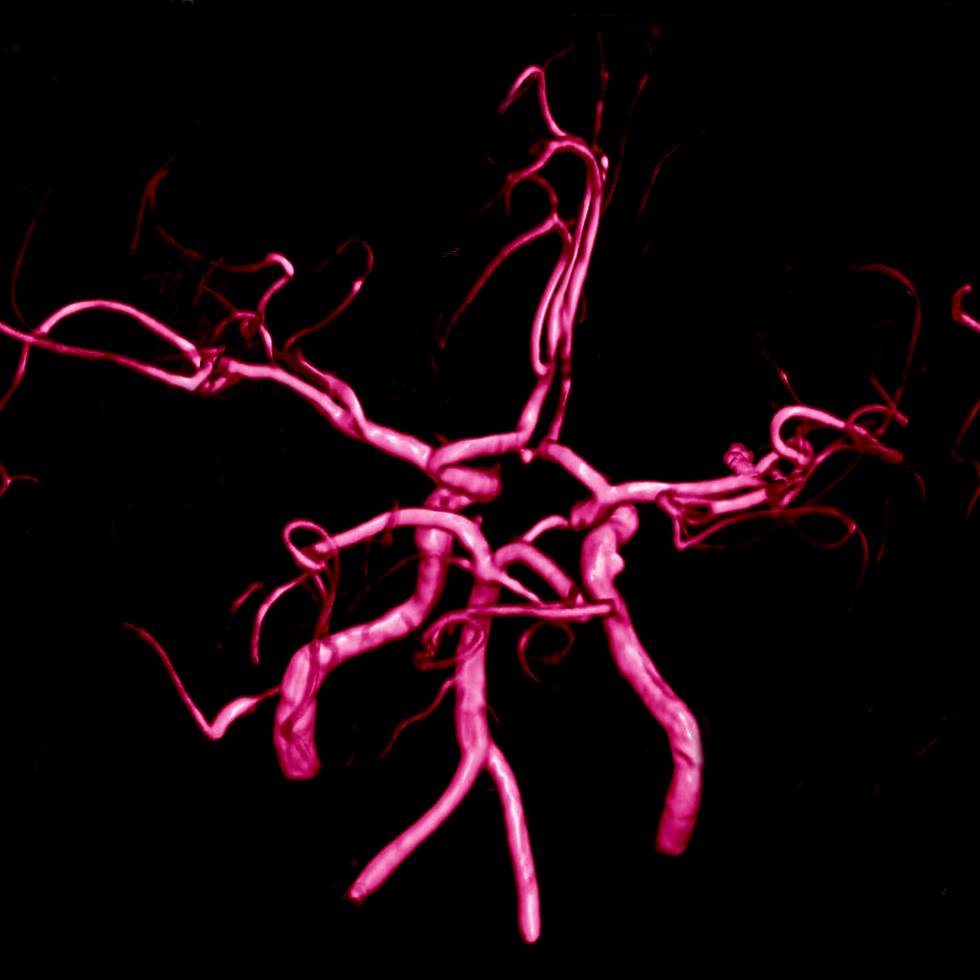

I didn’t understand the delay at the time, but I know now that the surgery had to be planned very carefully due to the location of the tumour in the skull base. The exact medical term is intracranial epidermoid cyst, but tumour is less of a mouthful. This type of tumour is benign and congenital meaning it was there before I was born. As I grew, it grew. The bigger it got, the more problems I faced.

I had my first seizure aged ten, but I didn’t know it was a seizure and told nobody. I would be sixteen before I spoke to a doctor about episodes that were different types of seizure. Epilepsy is a complex disorder that takes many different forms. The types of seizure I have don’t involve me falling to the ground and shaking. I enter a trance-like state and become unresponsive. I’m unable to remember the seizure and experience confusion and tiredness afterwards. To a stranger, I would look absolutely fine and that is the most difficult part of an invisible disability. If people cannot see that you are unwell, the illness is often treated as less serious or even non-existent. As someone once said to me ‘you don’t have real seizures.’ My epilepsy is very real and has put limits on my life for more years than I care to count.

Cognitive impairment began in my mid-teens. I took a swan dive from the top of the class to close to the bottom. It was a miracle I made it to university at all. I also endured severe depression and personality changes. Nobody added all these symptoms up and thought brain tumour, but I was lucky in that one doctor recognised signs of epilepsy, which led to the discovery of the tumour. I can look back now and know that I didn’t become stupid at the age of fifteen, it was that the little monster inside my head was growing.

I picked up scraps of information about the tumour from eavesdropping when my mother spoke to doctors and the occasional straight answer from a medic. I learned that if I didn’t have surgery I would be terminally ill within a year. It would be a slow death, preceded by paralysis on the right side, protrusion of the tumour through the forehead, coma and then death by the age of twenty-three at best. My life was very much in the hands of my neurosurgeon who looked quite like Rod Stewart.

For reasons I can’t fully explain, I began to tell myself that the tumour wasn’t really in my brain, but rather just beside it. I was young, frightened and didn’t fully understand what was happening to me. Truth be told, nobody informed me that my brain was already damaged and that the act of surgery would leave extensive damage behind.

It was explained that part of my skull would be removed to access my brain and remove the tumour. Gluing the bone back in place created a step in my skull and every time I touch it, I’m reminded of what happened. I was also told that half my head would be shaved which hit me like a ton of bricks. I walked into the hospital with long, auburn curls and found it hard to imagine that they’d be taken away while I was under anaesthetic.

A few months prior, I’d read an article about a woman who documented her brain tumour and I asked my neurosurgeon if I could have my surgery photographed and he agreed. I wanted to see what the tumour looked like and what my brain looked like. I still have the photos, but it’s quite rare that I sit and look at them. If I do look at them, I feel grateful for surviving, but also saddened by the amount of damage that's been done.

On August 4th 1998, I was woken early by a nurse and told to wash my hair. I wondered then and I wonder now why it needed to be clean to be shaved off. I was sitting on the bed drying it when my parents appeared. I didn’t know why they were there as I hadn’t been given the impression that it was a gravely serious surgery. What I know now allows me to see it in a different light. They were present because there was a risk of death, serious complications and damage to things we all take for granted such as seeing, hearing, walking and talking.

I remember being put to sleep in an ante-room and the next thing I knew, my neurosurgeon was asking me if I could see with my left eye in recovery. Thankfully, I could. I would learn later that part of the tumour had been attached to the left optic nerve.

The worst part of the hospital stay was the swelling pain after the drain was removed. It was excruciating. I remember clasping both hands against my head and curling in and out of a fetal position until tears were running down my face. All I wanted to do was scream from agony until the swelling stopped. Another patient politely told me that one side of my head had doubled in size. It reduced to normal proportions over a few days. The second worst was looking in the mirror and seeing half my hair gone and the other half matted with blood. After discharge, a lot of that had to be cut off too.

I spent two weeks in hospital and even appeared at a neurosurgery conference feeling like a bit of a curiosity, but apparently what was in my head is exceedingly rare. It was also rather large, my neurosurgeon said the tumour was the size of a satsuma. I haven’t eaten one since.

Years later, I read an MRI report and learned that the tumour had a diameter of 7cm. It’s hard to imagine something that big fitting inside my head.

All my life when I opened my eyes, I could see my nose and I thought this was perfectly normal. As it had never been any other way, I naturally assumed that everyone could see their nose. You can imagine my surprise when I learned that the opposite is true. I found it hard to believe that other people can’t see their noses without a mirror. That small difference in my eyesight was the first sign of the presence of the tumour. An eye specialist called it a nasal deficit and told me I had decreased peripheral vision on the left. That was less of a surprise as I knew that I didn’t see as well on that side and if anybody wants to give me a fright all they have to do is approach me from the left.

On the day of discharge, I was given instructions about wound care and using baby shampoo for a few weeks. There were no warnings about the consequences of a tumour and neurosurgery in the long term. I walked out considering myself fixed because the operation had been successful. The term ‘acquired brain injury’ or ABI for short was never uttered in my presence and it would be another twenty-five years before I came to understand how it applies to me.

A small part of me was hoping that the removal of the tumour would mean my seizures would also disappear, but that wasn’t to be the case. The tumour’s biggest gift to me is epilepsy that remains difficult to control and during bad patches, limits what I can do.

Within six weeks of the surgery, I returned to university and tried to get on with things as best I could. It was difficult always being in a hat to hide the fact that half my hair was just starting to regrow. News of my surgery had spread like wildfire through the university and I heard whispers wherever I went. It would take many months to shake off the feeling of being stared at and labelled as someone who had a brain tumour.

Gradually I noticed that some things were different and that I couldn’t do things in the way I had before. I became highly sensitive to noise, allergic to busy areas and parties, sensitive to bright lights, more prone to stress and feeling overwhelmed by things that had never bothered me before. I had a part-time job in a pub, but found it unbearable and was forced to quit. I know now the issues are neuro-fatigue and sensory overload, but that language was unavailable to me at the time so I told nobody what I was experiencing.

I told myself that it must be linked to my epilepsy even when my seizures were well controlled. I thought it couldn’t be anything to do with the tumour because the hospital fixed me. I spent a lot of time feeling like I was going mad.

Despite those obstacles, I completed my primary degree and went on to complete a Master’s degree for which I was awarded a fellowship. While the left side of my brain is damaged, my core intelligence remains unchanged and that’s a blessing I remain grateful for every day.

Last Summer, twenty-five years after neurosurgery, I began a program of rehabilitation for ABI and years of confusion about physical, cognitive, social and emotional problems are starting to make sense. There’s a huge relief in knowing for certain that I was never going mad.

ABI is a bit like an iceberg, most of the problems are hidden beneath the surface and when you look fine, as I did and do, most people assume you’re fine.

My mindset was always geared toward fixing the problems I have. I wanted to fix my epilepsy and the other issues related to having an ABI so that I would then be able to have a normal life, just like everybody else. I wanted to be fine, instead of just pretending I was.

I have read MRI reports that detail extensive scarring and white matter abnormality in my left frontal lobe and left temporal lobe. This is the presumed cause of my epilepsy. This damage will always be with me and there is no repairing it.

It is difficult to accept that these problems cannot be fixed. The solution lies in learning how to live with them and utilise strategies to make life easier and achieve my priorities. There’s also great comfort and support in friendships made with other people who live with an ABI.

It would be easy to spend a lifetime grieving for all that I’ve lost due to neurological conditions, but I’ve spent enough time in mourning. I’m choosing to believe that while the tumour left me with obstacles, I can build a life with those obstacles in mind, rather than being a prisoner to them.

Much of who I am as a person is linked to my experience of epilepsy and ABI as I have lived longer with them than I have without them. I have no doubt that I’d be different if neither of those things had befallen me.

I believe that the combination of these two things grants me a perspective that is unique. A perspective that influences my writing whether it be fiction or nonfiction. Down through the years, writing has always been my saviour and it’s a cornerstone of my identity. When times get tough, writing is my safety rope.

My ABI is an open wound that has never wanted to heal, but if life has taught me anything, it’s that I am a survivor. I possess the determination necessary to discover the best means of putting the little monster that once lay inside my head to rest permanently.

Comments